SAIL TO SCAR CRAGS

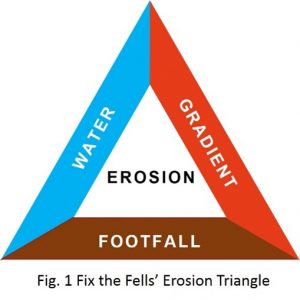

Firefighters often refer to the “Fire Triangle” when explaining how they tackle fires. A fire needs three elements to keep burning – fuel, heat and oxygen – and firefighting techniques are aimed at removing one or more of these elements.

Fix the Fells tackle man-made erosion on the upland paths in the Lake District and imagine a similar triangle with three different factors that cause erosion – water, footfall and gradient. When we consider the best technique to tackle erosion on a particular path, we have to work out what we can do about each of these elements, whilst leaving as little trace of our work as possible.

In reality, we have limited control over rainfall, numbers of visitors and the steepness of the fells. The first two factors have increased significantly in recent years, with more extreme weather events and more people holidaying in the UK. However, we manage the issues as best we can:

- We use side ditches where necessary to keep water off paths and the camber of the path and cross drains to get rid of water that ends up on the path.

- We try to reduce the impact of footfall by trying to keep people on the sustainable line, which is protected by a hard wearing surface, stone pitching or aggregate, where necessary.

- In general, gentler path gradients are more resistant to erosion than steeper slopes for two reasons. Firstly, path surfaces are more stable on gentler slopes. Secondly, slower water has less power to damage the path surface and is easier to direct off the path.

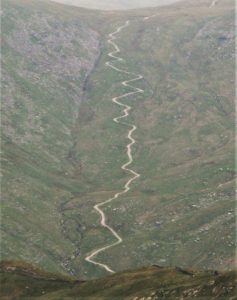

This case study looks at the particular factors that were taken into account when considering the best way to tackle the severe erosion on the Sail to Scar Crags path, either side of the col that lies between these two Wainwright summits. The route is very popular, forming part of a number of popular circuits from both Buttermere and Newlands valleys. The path that had developed on both sides of the col followed a so-called “desire line” with a steep gradient straight up the fell.